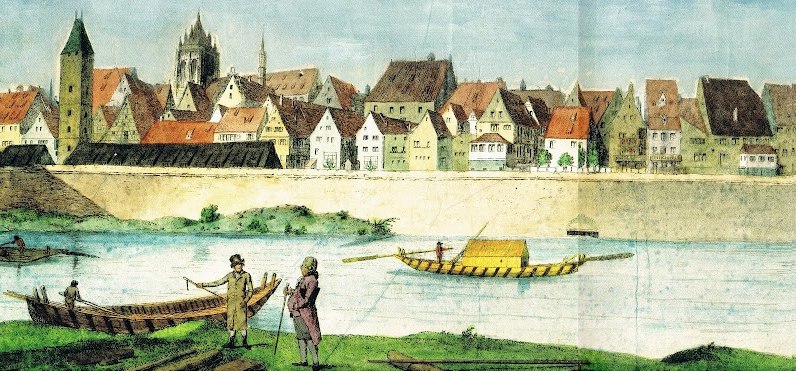

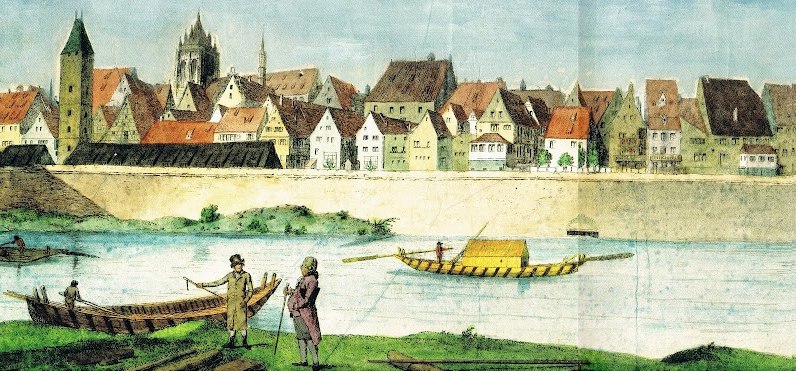

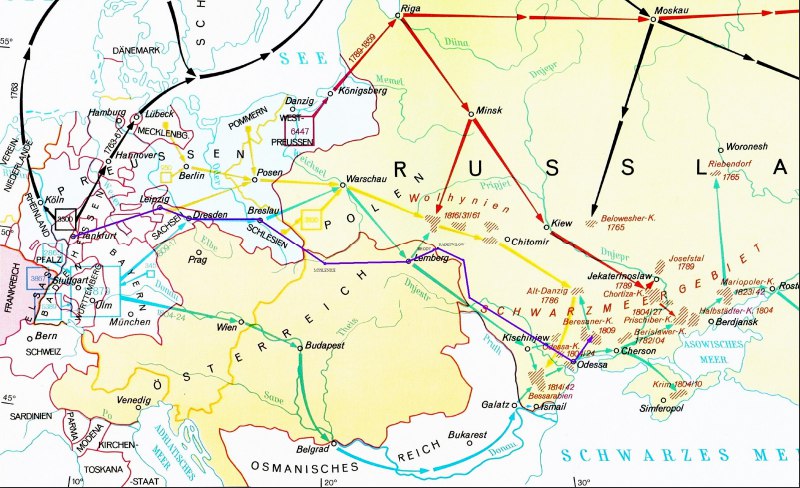

The organized settlement of Germans in Ukraine began in 1767, when 173 families of peasants and artisans arrived in the Chernihiv Governorate. They had originally been intended for the Volga region. Six German colonies were founded in the Bilovezh steppe and became known as the “Bilovezh colonies.” Following the example of Hungarian magnates, some landowners in Little Russia and the Black Sea region—such as P. Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky, O. Prozorovsky, and G. Potemkin—invited Germans to their estates to develop agriculture and crafts. However, this practice did not become widespread. In 1787–1788, more than 2,000 Mennonites and Lutherans from Danzig were recruited as state settlers to the former lands of the Zaporizhian Cossacks, which had been incorporated into the imperial treasury. They were enlisted in Danzig and the surrounding area by Assessor Trappe, acting on the orders of Prince Potemkin. The Mennonites were allocated land in the tract and on Khortytsia, while the Lutherans settled near Yelisavetgrad (Old Danzig) and Katerynoslav (Josefstal and Fischerdorf).

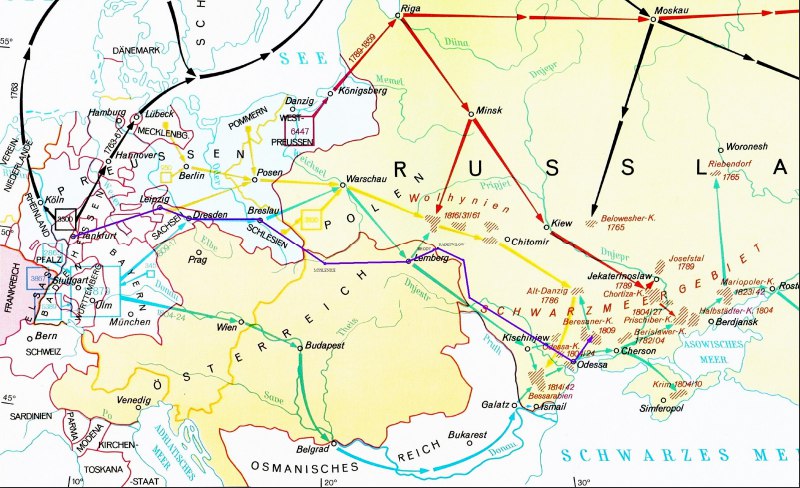

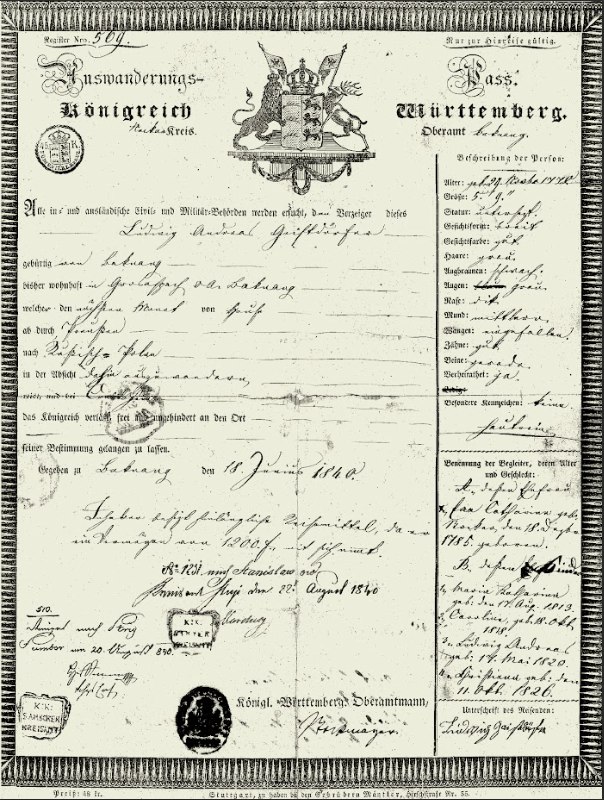

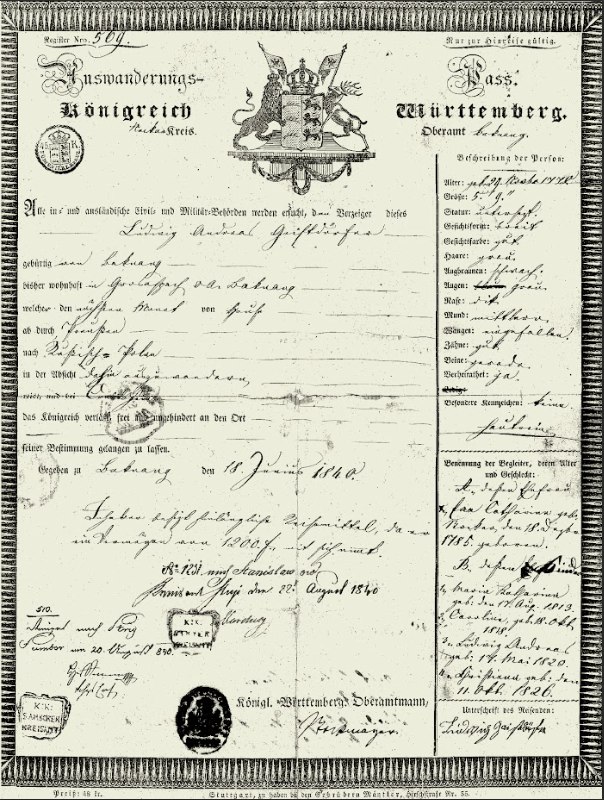

The Napoleonic Wars placed a heavy burden on the populations of Württemberg, Baden, Alsace, Hesse-Darmstadt, the Palatinate, Prussia, and neighboring states. As a result, many developed aspirations to emigrate and sought more favorable living conditions. The equalization of rights for subjects in the young Kingdom of Württemberg—and especially the church reform—provoked discontent among Pietists, who wished to live under a more tolerant rule. The fertile lands of the Taurida region in the Black Sea area, together with freedom of religion, attracted those dissatisfied with their situation.

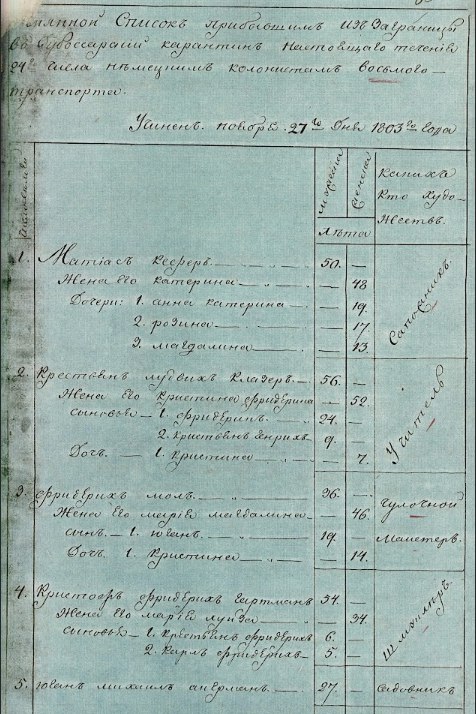

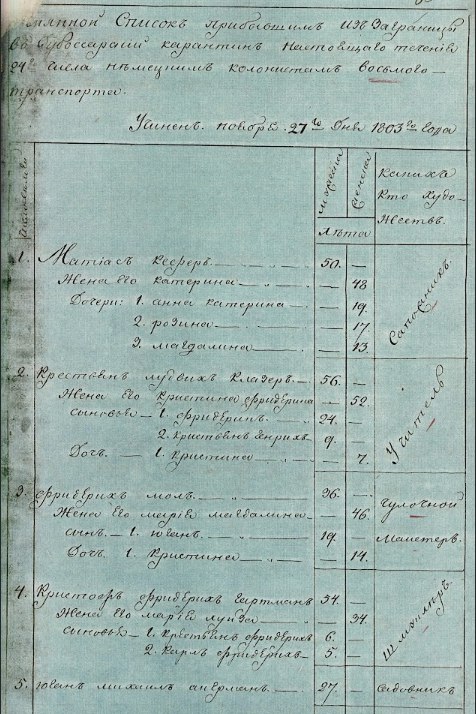

When settlers were admitted to the Northern Black Sea region in the 19th century, the mistakes and difficulties of the Volga colonization were taken into account. In 1804, Alexander I approved new regulations for the settlement of foreigners. Recruitment was carried out in limited numbers through Russian diplomatic missions abroad. The colonists were required to possess farming or craft skills as well as a certain amount of money. They were sent in groups, mainly by ship along the Danube to Galați, or overland through Europe to Odesa and Katerynoslav, and from there were directed to their designated places of settlement.

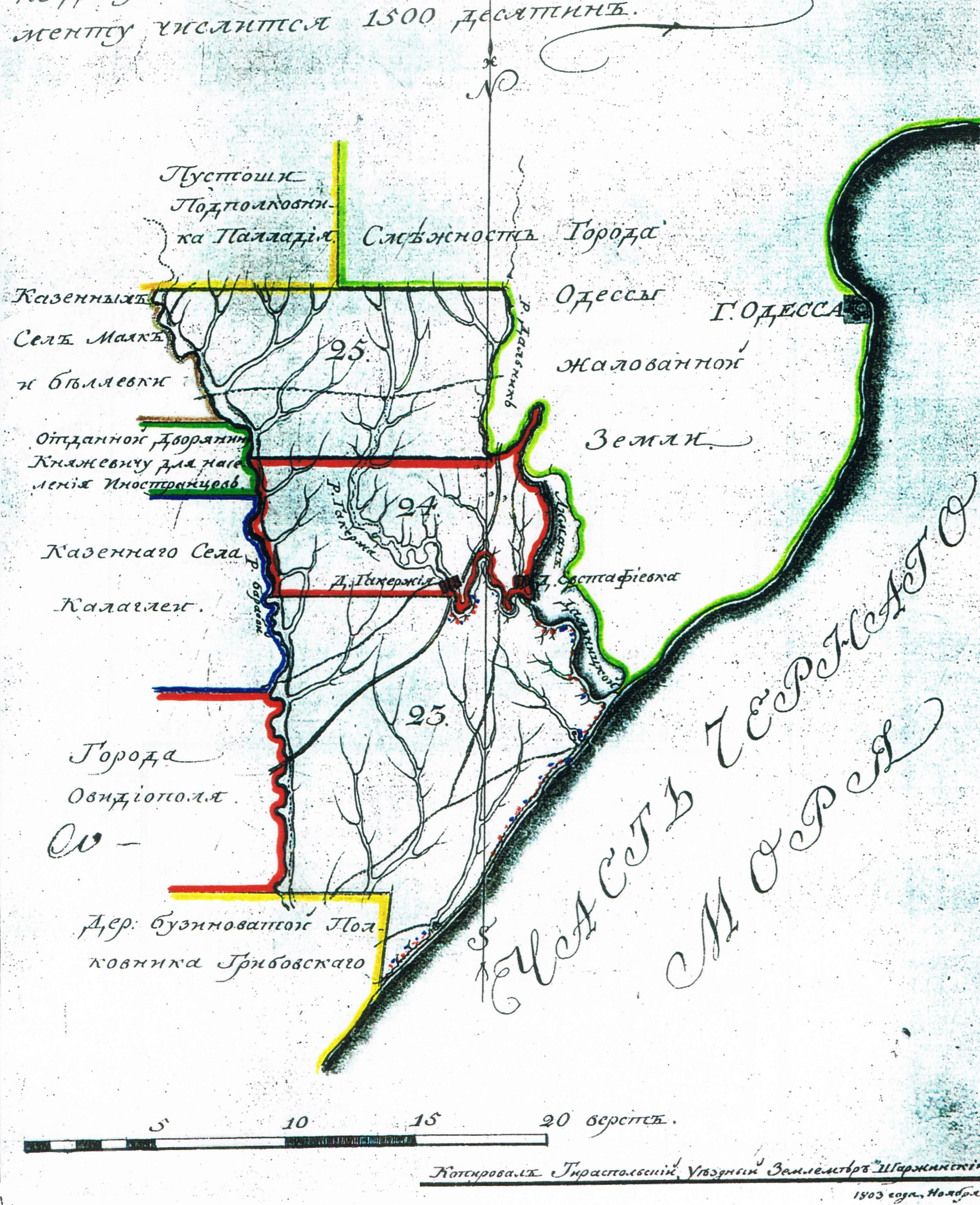

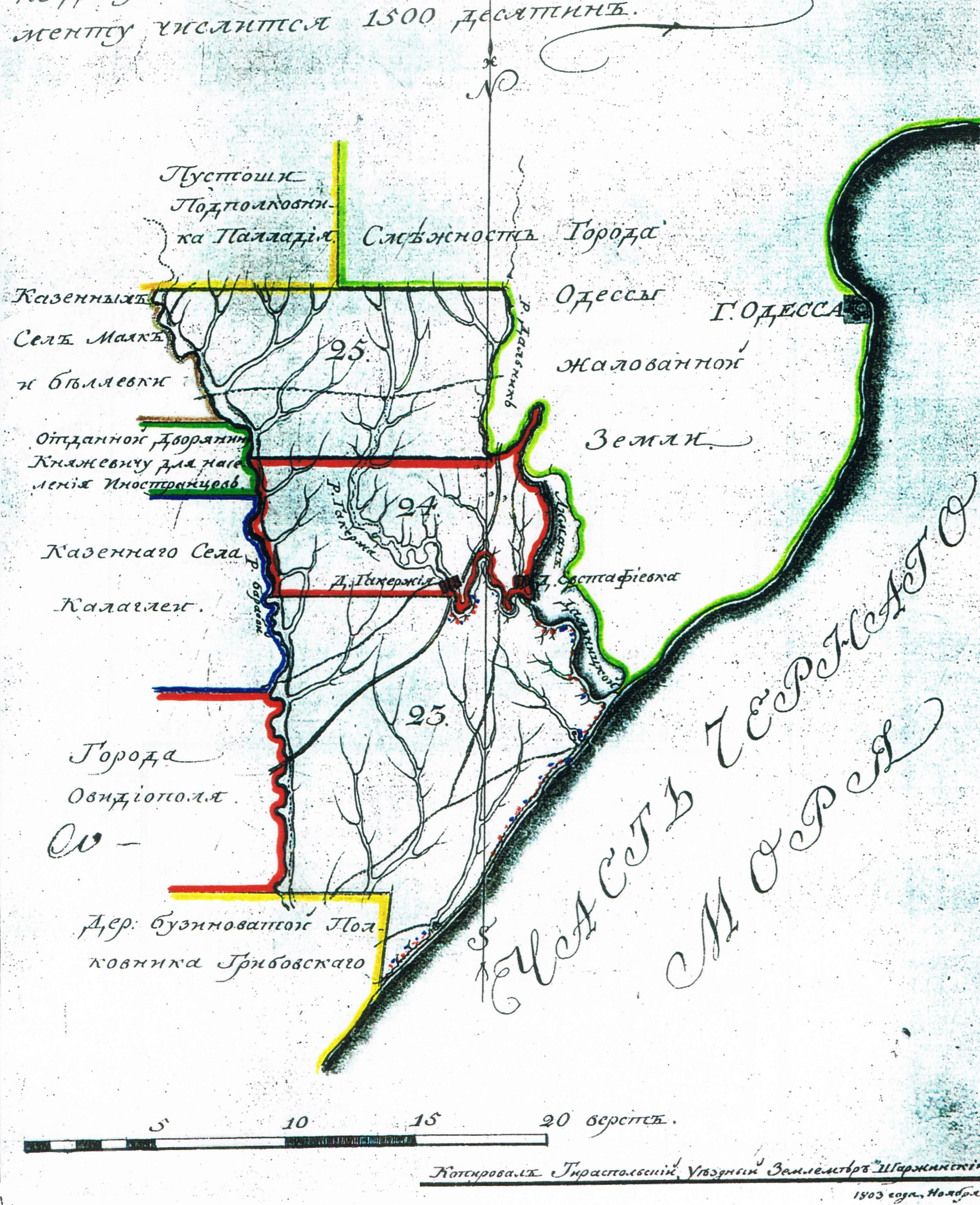

To facilitate the settlement of compact groups, the government allocated state-owned land and purchased undeveloped land from landowners, providing funding for construction and the establishment of farms. The colonists were required to repay these expenses to the treasury. The main benefits granted to the new settlers included freedom of religion, a land grant of 60 desiatinas, lifelong exemption from military service, and a 10-year deferment on taxes and debts. Starting from scratch, they endured harsh conditions in the early years, which often led to illness and death.

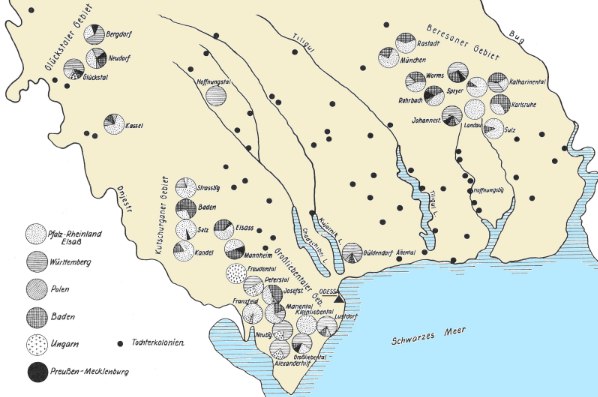

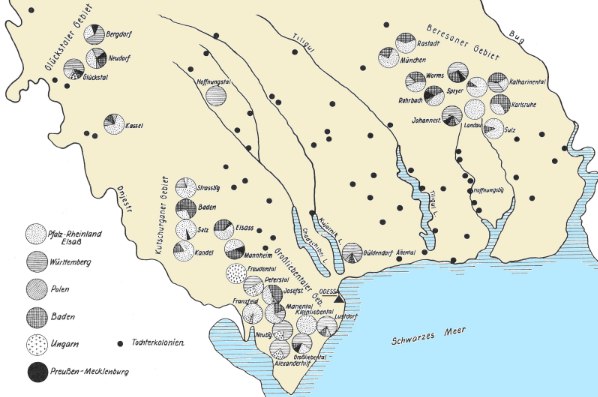

As a result of several waves of migration to the south in the early 19th century, compact agricultural settlements were established in the Kherson Governorate—near Odesa, Mykolaiv, Beryslav, and Hryhoriopol—and in the Taurida and Katerynoslav Governorates, along the Molochna River, in Crimea, and in Mariupol and Berdyansk regions.

By the mid-19th century, these governorates counted 170 “mother colonies” with a population of over 85,000. Following the revolutionary events in Europe, the further settlement of colonists was prohibited in 1848.

The Black Sea territories between the Bug and Dniester rivers, annexed by Russia in 1791 after being conquered from Turkey, required economic development to secure the new borders and support the growth of cities and ports such as Odesa and Mykolaiv. However, the first decade yielded little progress. To address this, foreign colonists were once again invited and allocated state-owned land, either purchased from or confiscated from landowners who had failed to cultivate it. Thanks to immigrants from Württemberg, Baden, the Palatinate, Alsace, Prussia, and Hungary, agricultural colonies such as Mannheim, Kandel, München, Kassel, Speyer, Rastatt, Rohrbach, Karlsruhe, Worms, and Sulz appeared in the steppes of the Kherson Governorate between 1804–1810 and 1817–1821. By the time of their liquidation in 1871, four colonial districts near Odesa, Mykolaiv, and Hryhoriopol covered more than 160,000 desiatinas and included 32 colonies with a population of about 55,000 people.

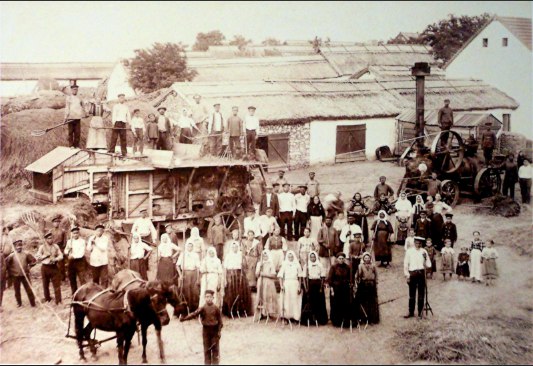

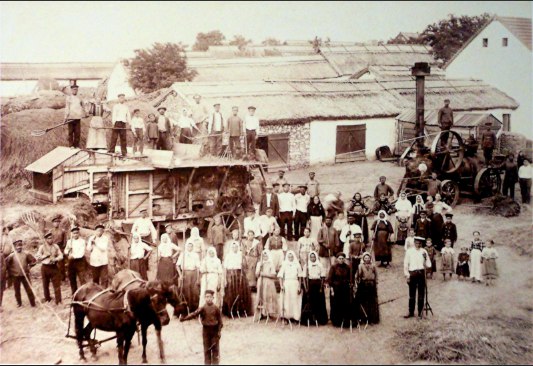

Having found themselves in the uninhabited steppe, a zone of risky agriculture, the colonists faced a multitude of challenges in cultivating the land. They were unfamiliar with Russian legislation, the language, and the natural environment, often lacked the necessary skills, and had only limited contact outside their colonies. The adaptation period stretched over decades. Each family received 60 desiatinas of land, but at first only 2–3 were plowed and sown. The heavy, unwieldy wooden plow was shared by 2–3 households, required 6–8 oxen to pull, and needed three plowmen to keep it in the furrow. By 1848, every farmer in the Beresan district already owned an iron horse-drawn plow, while the more prosperous had two.

The main branches of the economy were grain farming, animal husbandry, vegetable growing, and horticulture. The first signs of cooperation appeared in 1847 in Glückstal, where 23 determined farmers built a cheese factory to increase profits from livestock. That year, they produced 360 poods of cheese. By 1852, the total income of all districts from the sale of grain, products, and wool amounted to 614,000 silver rubles. Viticulture and winemaking developed more intensively in these colonies than in other foreign settlements. Colonists began to equip their homes with wine cellars. In 1841, the Liebental district had 3.3 million grapevines, while the Glückstal district had 1.2 million (39% of the total number of vines in foreign colonies). Their harvest yielded nearly 1.5 million liters of wine. By the beginning of the 20th century, the Germans maintained their leadership in the region, owning 3,000 vineyards covering 1,000 dessiatinas.

Although Mennonite artisans were renowned for their craftsmanship, priority in plow innovation belongs to Konrad Bechtold of the Liebental district (Freudental), who invented a number of plows and other tools. He improved the Little Russian plow and took first place at the plow trials in Odesa in 1840. The all-metal “Bechtold plow” spread rapidly.

In Freudental alone, 167 plows were produced in 1852—almost as many as in the Molochna Mennonite district. In 1858, a large number were sent to Molochna. In the Liebental colonies, a rural settlement infrastructure was developed to meet the population’s needs and support its growth.

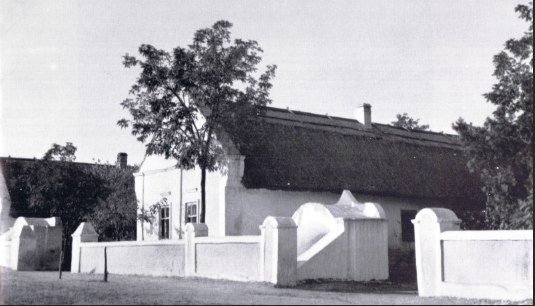

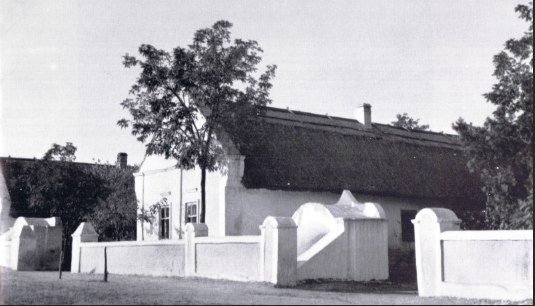

It included a church, a parsonage, a school, a village administration, public sources of drinking water, and a reserve grain storehouse (“magazin”). In the main colony, there was also a district office and the supervisor’s residence. This system was introduced in all foreign colonies. Settlement planning was orderly and primarily linear.

Construction relied on local building materials such as coquina, limestone, and clay, which the colonists quarried themselves. Public quarries were found in nearly all the colonies of the Black Sea region.

As early as 1809, a fire insurance fund was established in Gross Liebental. Losses from fire were compensated to the affected household by all landowners in proportion to the value of their own buildings.

The name “Gross Liebental” was also given to a meteorite that fell near the colony in 1881. Festive celebrations marking the 100th anniversary of its founding were held in all the Black Sea colonies.

The rights and privileges granted to the colonists, along with a special system of colonial administration based on the principle of trusteeship, facilitated their settlement and development. The colonists were subject to five levels of oversight: elected officials, overseers, trustee bodies, the church, and general state institutions. A group of colonies constituted a colonial district. By the mid-19th century, there were 16 German and Mennonite districts.

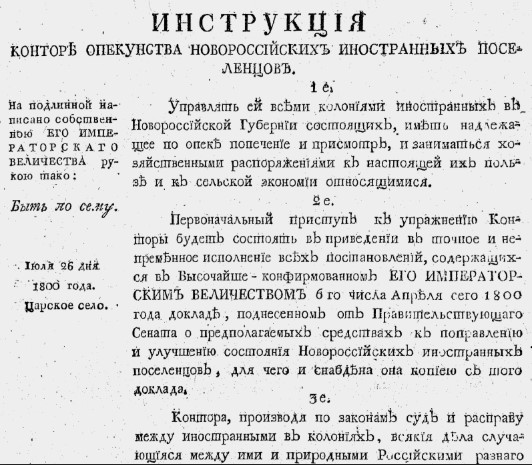

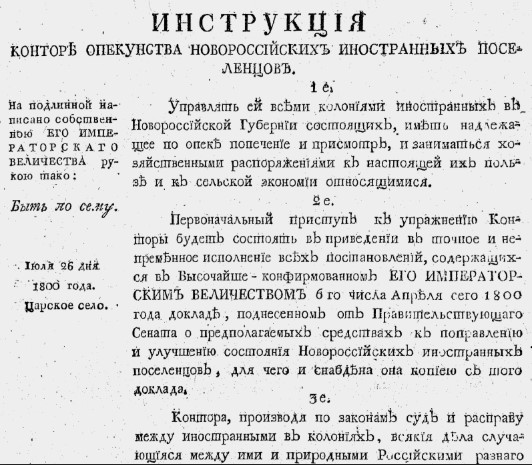

A Guardianship Office was established in Katerynoslav in 1800 for administrative purposes. Its functions were regulated by an instruction issued the same year, and its first head was Samuel Contenius, a Silesian (1800–1818). The districts and colonies were governed through resident colonial overseers and an approved leadership of Oberschulzen, Amtsbeisitzern, Dorfschulzen, and Beisitzern (mayors and their assistants), who were elected from among the most prominent colonists. Their activities were defined by the Instruction on the Internal Order of the Colonies (1801), which remained in effect for seventy years. In each colony, a rural office headed by a Schulzen was established, while the main colony of each district housed the district office, headed by an Oberschulze. These officials were entrusted with fiscal and police responsibilities and authorized to resolve minor disputes among the colonists. Discipline and diligence were regarded as the foundation of economic development. The lazy, negligent, and disobedient faced punishments ranging from corporal punishment and confiscation of property to exile to Siberia or expulsion abroad as a deterrent to others. As the executors of colonial leadership’s decisions in all spheres of life, the elected officials were accountable to it and responsible for conditions in the colonies. This system of self-government remained in place until 1871.

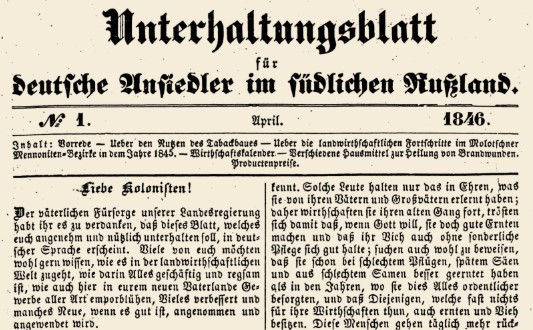

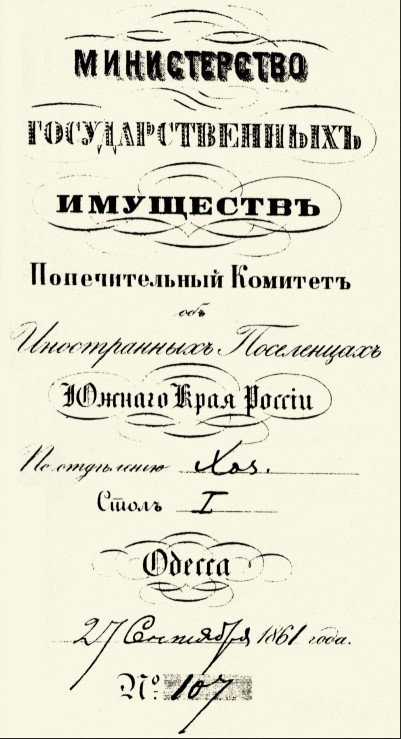

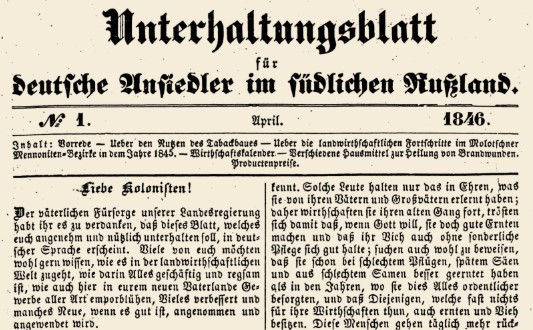

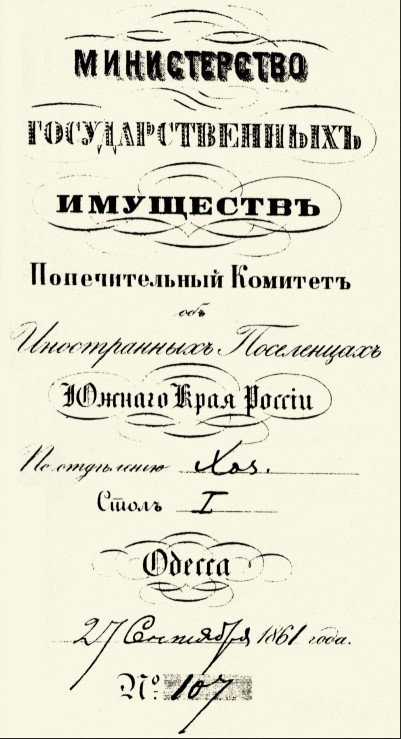

With the growth in the number of settlements, a new institution was established—the Guardianship Committee for Foreign Settlers of the Southern Region of Russia (1818). It oversaw all foreign colonies within the Kherson, Katerynoslav, and Taurida governorates, as well as the Bessarabia region. In addition to managing the organization of colonies and supporting their economic development, the committee was granted powers equal to those of the provincial administrations, including supervisory, fiscal, police, judicial, and correctional functions. It was subordinate to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and, from 1837, to the Ministry of State Domains. Administration was carried out through three guardianship offices in Odesa, Katerynoslav, and Căușeni (1818–1833), as well as through overseers and elected officials. The committee was headed mainly by Baltic Germans, including E. von Hahn, Baron von Rosen, Baron von Mestmacher, A. von Hamm, F. von Lysander, and V. von Oettinger. The committee analyzed the economic activities of the colonies and, to disseminate specialized and innovative knowledge in agriculture and crafts among the German colonists, published a German-language newspaper from 1846 to 1862.

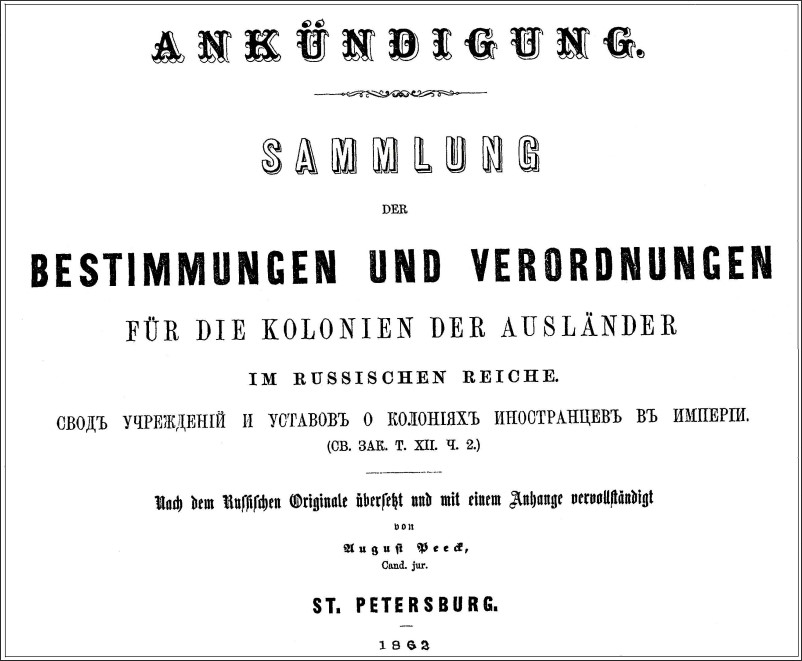

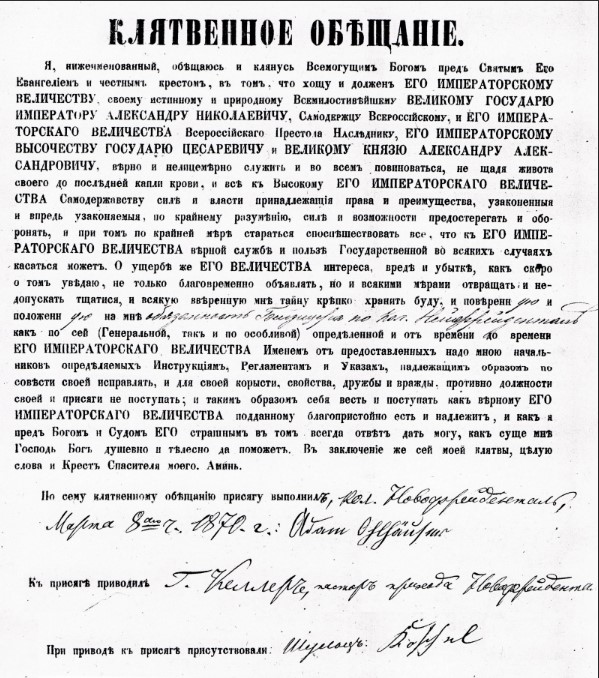

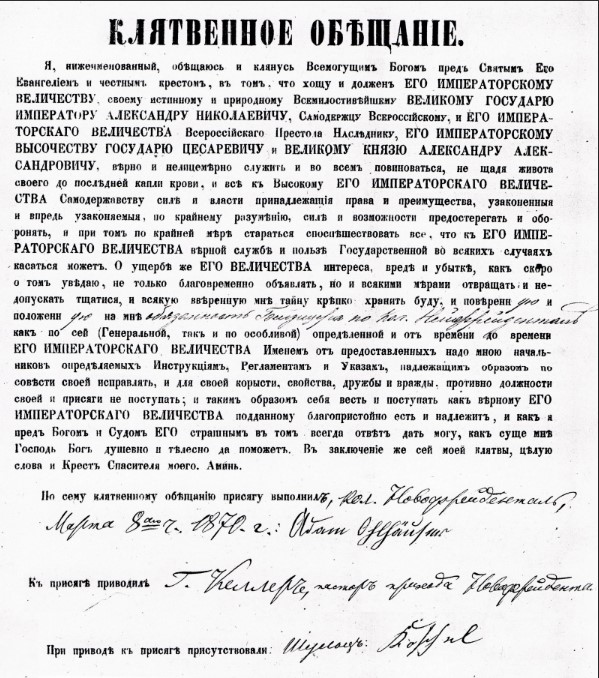

As subjects of the Russian Empire, German colonists were bound by the general norms of Russian law, just like state peasants.

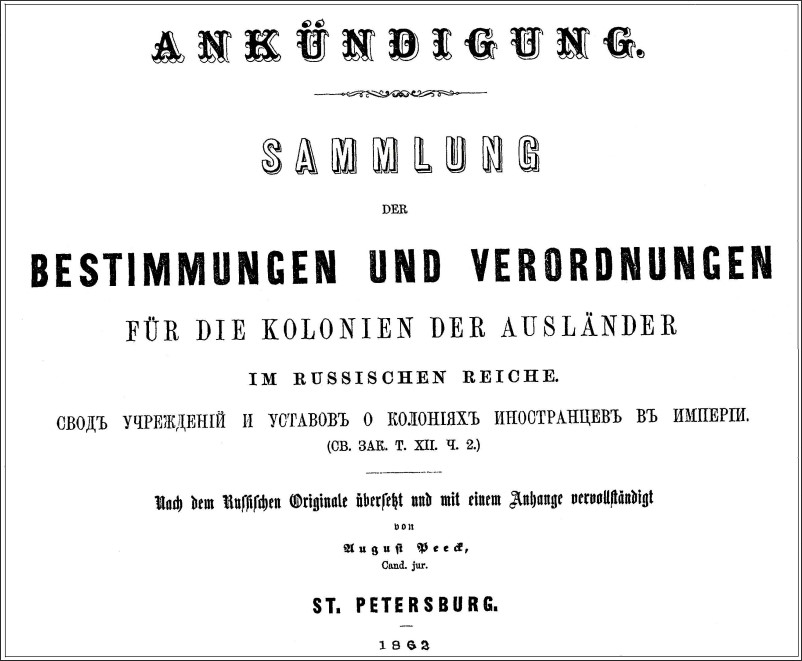

The legislative acts regulating colonial life were consolidated in the Statute on Foreigners’ Colonies in the Empire (1857).

In 1871, radical changes transformed the status of the colonists and their administration: they became peasant-proprietors, the guardianship bodies were abolished, the colonial districts dissolved, and volosts were established in their place. Administration was henceforth carried out by the regular provincial and county authorities.

By that time, in the three governorates, there were more than 190 German colonies with a population of 150,000 people of both sexes on state-owned lands, and nearly as many colonies on purchased and leased lands. In total, they possessed more than one million desyatinas of land.

The organized settlement of Germans in Ukraine began in 1767, when 173 families of peasants and artisans arrived in the Chernihiv Governorate. They had originally been intended for the Volga region. Six German colonies were founded in the Bilovezh steppe and became known as the “Bilovezh colonies.” Following the example of Hungarian magnates, some landowners in Little Russia and the Black Sea region—such as P. Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky, O. Prozorovsky, and G. Potemkin—invited Germans to their estates to develop agriculture and crafts. However, this practice did not become widespread. In 1787–1788, more than 2,000 Mennonites and Lutherans from Danzig were recruited as state settlers to the former lands of the Zaporizhian Cossacks, which had been incorporated into the imperial treasury. They were enlisted in Danzig and the surrounding area by Assessor Trappe, acting on the orders of Prince Potemkin. The Mennonites were allocated land in the tract and on Khortytsia, while the Lutherans settled near Yelisavetgrad (Old Danzig) and Katerynoslav (Josefstal and Fischerdorf).

The organized settlement of Germans in Ukraine began in 1767, when 173 families of peasants and artisans arrived in the Chernihiv Governorate. They had originally been intended for the Volga region. Six German colonies were founded in the Bilovezh steppe and became known as the “Bilovezh colonies.” Following the example of Hungarian magnates, some landowners in Little Russia and the Black Sea region—such as P. Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky, O. Prozorovsky, and G. Potemkin—invited Germans to their estates to develop agriculture and crafts. However, this practice did not become widespread. In 1787–1788, more than 2,000 Mennonites and Lutherans from Danzig were recruited as state settlers to the former lands of the Zaporizhian Cossacks, which had been incorporated into the imperial treasury. They were enlisted in Danzig and the surrounding area by Assessor Trappe, acting on the orders of Prince Potemkin. The Mennonites were allocated land in the tract and on Khortytsia, while the Lutherans settled near Yelisavetgrad (Old Danzig) and Katerynoslav (Josefstal and Fischerdorf). The Napoleonic Wars placed a heavy burden on the populations of Württemberg, Baden, Alsace, Hesse-Darmstadt, the Palatinate, Prussia, and neighboring states. As a result, many developed aspirations to emigrate and sought more favorable living conditions. The equalization of rights for subjects in the young Kingdom of Württemberg—and especially the church reform—provoked discontent among Pietists, who wished to live under a more tolerant rule. The fertile lands of the Taurida region in the Black Sea area, together with freedom of religion, attracted those dissatisfied with their situation.

The Napoleonic Wars placed a heavy burden on the populations of Württemberg, Baden, Alsace, Hesse-Darmstadt, the Palatinate, Prussia, and neighboring states. As a result, many developed aspirations to emigrate and sought more favorable living conditions. The equalization of rights for subjects in the young Kingdom of Württemberg—and especially the church reform—provoked discontent among Pietists, who wished to live under a more tolerant rule. The fertile lands of the Taurida region in the Black Sea area, together with freedom of religion, attracted those dissatisfied with their situation. When settlers were admitted to the Northern Black Sea region in the 19th century, the mistakes and difficulties of the Volga colonization were taken into account. In 1804, Alexander I approved new regulations for the settlement of foreigners. Recruitment was carried out in limited numbers through Russian diplomatic missions abroad. The colonists were required to possess farming or craft skills as well as a certain amount of money. They were sent in groups, mainly by ship along the Danube to Galați, or overland through Europe to Odesa and Katerynoslav, and from there were directed to their designated places of settlement.

When settlers were admitted to the Northern Black Sea region in the 19th century, the mistakes and difficulties of the Volga colonization were taken into account. In 1804, Alexander I approved new regulations for the settlement of foreigners. Recruitment was carried out in limited numbers through Russian diplomatic missions abroad. The colonists were required to possess farming or craft skills as well as a certain amount of money. They were sent in groups, mainly by ship along the Danube to Galați, or overland through Europe to Odesa and Katerynoslav, and from there were directed to their designated places of settlement. To facilitate the settlement of compact groups, the government allocated state-owned land and purchased undeveloped land from landowners, providing funding for construction and the establishment of farms. The colonists were required to repay these expenses to the treasury. The main benefits granted to the new settlers included freedom of religion, a land grant of 60 desiatinas, lifelong exemption from military service, and a 10-year deferment on taxes and debts. Starting from scratch, they endured harsh conditions in the early years, which often led to illness and death.

To facilitate the settlement of compact groups, the government allocated state-owned land and purchased undeveloped land from landowners, providing funding for construction and the establishment of farms. The colonists were required to repay these expenses to the treasury. The main benefits granted to the new settlers included freedom of religion, a land grant of 60 desiatinas, lifelong exemption from military service, and a 10-year deferment on taxes and debts. Starting from scratch, they endured harsh conditions in the early years, which often led to illness and death. As a result of several waves of migration to the south in the early 19th century, compact agricultural settlements were established in the Kherson Governorate—near Odesa, Mykolaiv, Beryslav, and Hryhoriopol—and in the Taurida and Katerynoslav Governorates, along the Molochna River, in Crimea, and in Mariupol and Berdyansk regions.

As a result of several waves of migration to the south in the early 19th century, compact agricultural settlements were established in the Kherson Governorate—near Odesa, Mykolaiv, Beryslav, and Hryhoriopol—and in the Taurida and Katerynoslav Governorates, along the Molochna River, in Crimea, and in Mariupol and Berdyansk regions. By the mid-19th century, these governorates counted 170 “mother colonies” with a population of over 85,000. Following the revolutionary events in Europe, the further settlement of colonists was prohibited in 1848.

By the mid-19th century, these governorates counted 170 “mother colonies” with a population of over 85,000. Following the revolutionary events in Europe, the further settlement of colonists was prohibited in 1848. The Black Sea territories between the Bug and Dniester rivers, annexed by Russia in 1791 after being conquered from Turkey, required economic development to secure the new borders and support the growth of cities and ports such as Odesa and Mykolaiv. However, the first decade yielded little progress. To address this, foreign colonists were once again invited and allocated state-owned land, either purchased from or confiscated from landowners who had failed to cultivate it. Thanks to immigrants from Württemberg, Baden, the Palatinate, Alsace, Prussia, and Hungary, agricultural colonies such as Mannheim, Kandel, München, Kassel, Speyer, Rastatt, Rohrbach, Karlsruhe, Worms, and Sulz appeared in the steppes of the Kherson Governorate between 1804–1810 and 1817–1821. By the time of their liquidation in 1871, four colonial districts near Odesa, Mykolaiv, and Hryhoriopol covered more than 160,000 desiatinas and included 32 colonies with a population of about 55,000 people.

The Black Sea territories between the Bug and Dniester rivers, annexed by Russia in 1791 after being conquered from Turkey, required economic development to secure the new borders and support the growth of cities and ports such as Odesa and Mykolaiv. However, the first decade yielded little progress. To address this, foreign colonists were once again invited and allocated state-owned land, either purchased from or confiscated from landowners who had failed to cultivate it. Thanks to immigrants from Württemberg, Baden, the Palatinate, Alsace, Prussia, and Hungary, agricultural colonies such as Mannheim, Kandel, München, Kassel, Speyer, Rastatt, Rohrbach, Karlsruhe, Worms, and Sulz appeared in the steppes of the Kherson Governorate between 1804–1810 and 1817–1821. By the time of their liquidation in 1871, four colonial districts near Odesa, Mykolaiv, and Hryhoriopol covered more than 160,000 desiatinas and included 32 colonies with a population of about 55,000 people. Having found themselves in the uninhabited steppe, a zone of risky agriculture, the colonists faced a multitude of challenges in cultivating the land. They were unfamiliar with Russian legislation, the language, and the natural environment, often lacked the necessary skills, and had only limited contact outside their colonies. The adaptation period stretched over decades. Each family received 60 desiatinas of land, but at first only 2–3 were plowed and sown. The heavy, unwieldy wooden plow was shared by 2–3 households, required 6–8 oxen to pull, and needed three plowmen to keep it in the furrow. By 1848, every farmer in the Beresan district already owned an iron horse-drawn plow, while the more prosperous had two.

Having found themselves in the uninhabited steppe, a zone of risky agriculture, the colonists faced a multitude of challenges in cultivating the land. They were unfamiliar with Russian legislation, the language, and the natural environment, often lacked the necessary skills, and had only limited contact outside their colonies. The adaptation period stretched over decades. Each family received 60 desiatinas of land, but at first only 2–3 were plowed and sown. The heavy, unwieldy wooden plow was shared by 2–3 households, required 6–8 oxen to pull, and needed three plowmen to keep it in the furrow. By 1848, every farmer in the Beresan district already owned an iron horse-drawn plow, while the more prosperous had two. The main branches of the economy were grain farming, animal husbandry, vegetable growing, and horticulture. The first signs of cooperation appeared in 1847 in Glückstal, where 23 determined farmers built a cheese factory to increase profits from livestock. That year, they produced 360 poods of cheese. By 1852, the total income of all districts from the sale of grain, products, and wool amounted to 614,000 silver rubles. Viticulture and winemaking developed more intensively in these colonies than in other foreign settlements. Colonists began to equip their homes with wine cellars. In 1841, the Liebental district had 3.3 million grapevines, while the Glückstal district had 1.2 million (39% of the total number of vines in foreign colonies). Their harvest yielded nearly 1.5 million liters of wine. By the beginning of the 20th century, the Germans maintained their leadership in the region, owning 3,000 vineyards covering 1,000 dessiatinas.

The main branches of the economy were grain farming, animal husbandry, vegetable growing, and horticulture. The first signs of cooperation appeared in 1847 in Glückstal, where 23 determined farmers built a cheese factory to increase profits from livestock. That year, they produced 360 poods of cheese. By 1852, the total income of all districts from the sale of grain, products, and wool amounted to 614,000 silver rubles. Viticulture and winemaking developed more intensively in these colonies than in other foreign settlements. Colonists began to equip their homes with wine cellars. In 1841, the Liebental district had 3.3 million grapevines, while the Glückstal district had 1.2 million (39% of the total number of vines in foreign colonies). Their harvest yielded nearly 1.5 million liters of wine. By the beginning of the 20th century, the Germans maintained their leadership in the region, owning 3,000 vineyards covering 1,000 dessiatinas. Although Mennonite artisans were renowned for their craftsmanship, priority in plow innovation belongs to Konrad Bechtold of the Liebental district (Freudental), who invented a number of plows and other tools. He improved the Little Russian plow and took first place at the plow trials in Odesa in 1840. The all-metal “Bechtold plow” spread rapidly.

Although Mennonite artisans were renowned for their craftsmanship, priority in plow innovation belongs to Konrad Bechtold of the Liebental district (Freudental), who invented a number of plows and other tools. He improved the Little Russian plow and took first place at the plow trials in Odesa in 1840. The all-metal “Bechtold plow” spread rapidly. In Freudental alone, 167 plows were produced in 1852—almost as many as in the Molochna Mennonite district. In 1858, a large number were sent to Molochna. In the Liebental colonies, a rural settlement infrastructure was developed to meet the population’s needs and support its growth.

In Freudental alone, 167 plows were produced in 1852—almost as many as in the Molochna Mennonite district. In 1858, a large number were sent to Molochna. In the Liebental colonies, a rural settlement infrastructure was developed to meet the population’s needs and support its growth. It included a church, a parsonage, a school, a village administration, public sources of drinking water, and a reserve grain storehouse (“magazin”). In the main colony, there was also a district office and the supervisor’s residence. This system was introduced in all foreign colonies. Settlement planning was orderly and primarily linear.

It included a church, a parsonage, a school, a village administration, public sources of drinking water, and a reserve grain storehouse (“magazin”). In the main colony, there was also a district office and the supervisor’s residence. This system was introduced in all foreign colonies. Settlement planning was orderly and primarily linear. Construction relied on local building materials such as coquina, limestone, and clay, which the colonists quarried themselves. Public quarries were found in nearly all the colonies of the Black Sea region.

Construction relied on local building materials such as coquina, limestone, and clay, which the colonists quarried themselves. Public quarries were found in nearly all the colonies of the Black Sea region. As early as 1809, a fire insurance fund was established in Gross Liebental. Losses from fire were compensated to the affected household by all landowners in proportion to the value of their own buildings.

As early as 1809, a fire insurance fund was established in Gross Liebental. Losses from fire were compensated to the affected household by all landowners in proportion to the value of their own buildings. The name “Gross Liebental” was also given to a meteorite that fell near the colony in 1881. Festive celebrations marking the 100th anniversary of its founding were held in all the Black Sea colonies.

The name “Gross Liebental” was also given to a meteorite that fell near the colony in 1881. Festive celebrations marking the 100th anniversary of its founding were held in all the Black Sea colonies. The rights and privileges granted to the colonists, along with a special system of colonial administration based on the principle of trusteeship, facilitated their settlement and development. The colonists were subject to five levels of oversight: elected officials, overseers, trustee bodies, the church, and general state institutions. A group of colonies constituted a colonial district. By the mid-19th century, there were 16 German and Mennonite districts.

The rights and privileges granted to the colonists, along with a special system of colonial administration based on the principle of trusteeship, facilitated their settlement and development. The colonists were subject to five levels of oversight: elected officials, overseers, trustee bodies, the church, and general state institutions. A group of colonies constituted a colonial district. By the mid-19th century, there were 16 German and Mennonite districts. A Guardianship Office was established in Katerynoslav in 1800 for administrative purposes. Its functions were regulated by an instruction issued the same year, and its first head was Samuel Contenius, a Silesian (1800–1818). The districts and colonies were governed through resident colonial overseers and an approved leadership of Oberschulzen, Amtsbeisitzern, Dorfschulzen, and Beisitzern (mayors and their assistants), who were elected from among the most prominent colonists. Their activities were defined by the Instruction on the Internal Order of the Colonies (1801), which remained in effect for seventy years. In each colony, a rural office headed by a Schulzen was established, while the main colony of each district housed the district office, headed by an Oberschulze. These officials were entrusted with fiscal and police responsibilities and authorized to resolve minor disputes among the colonists. Discipline and diligence were regarded as the foundation of economic development. The lazy, negligent, and disobedient faced punishments ranging from corporal punishment and confiscation of property to exile to Siberia or expulsion abroad as a deterrent to others. As the executors of colonial leadership’s decisions in all spheres of life, the elected officials were accountable to it and responsible for conditions in the colonies. This system of self-government remained in place until 1871.

A Guardianship Office was established in Katerynoslav in 1800 for administrative purposes. Its functions were regulated by an instruction issued the same year, and its first head was Samuel Contenius, a Silesian (1800–1818). The districts and colonies were governed through resident colonial overseers and an approved leadership of Oberschulzen, Amtsbeisitzern, Dorfschulzen, and Beisitzern (mayors and their assistants), who were elected from among the most prominent colonists. Their activities were defined by the Instruction on the Internal Order of the Colonies (1801), which remained in effect for seventy years. In each colony, a rural office headed by a Schulzen was established, while the main colony of each district housed the district office, headed by an Oberschulze. These officials were entrusted with fiscal and police responsibilities and authorized to resolve minor disputes among the colonists. Discipline and diligence were regarded as the foundation of economic development. The lazy, negligent, and disobedient faced punishments ranging from corporal punishment and confiscation of property to exile to Siberia or expulsion abroad as a deterrent to others. As the executors of colonial leadership’s decisions in all spheres of life, the elected officials were accountable to it and responsible for conditions in the colonies. This system of self-government remained in place until 1871. With the growth in the number of settlements, a new institution was established—the Guardianship Committee for Foreign Settlers of the Southern Region of Russia (1818). It oversaw all foreign colonies within the Kherson, Katerynoslav, and Taurida governorates, as well as the Bessarabia region. In addition to managing the organization of colonies and supporting their economic development, the committee was granted powers equal to those of the provincial administrations, including supervisory, fiscal, police, judicial, and correctional functions. It was subordinate to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and, from 1837, to the Ministry of State Domains. Administration was carried out through three guardianship offices in Odesa, Katerynoslav, and Căușeni (1818–1833), as well as through overseers and elected officials. The committee was headed mainly by Baltic Germans, including E. von Hahn, Baron von Rosen, Baron von Mestmacher, A. von Hamm, F. von Lysander, and V. von Oettinger. The committee analyzed the economic activities of the colonies and, to disseminate specialized and innovative knowledge in agriculture and crafts among the German colonists, published a German-language newspaper from 1846 to 1862.

With the growth in the number of settlements, a new institution was established—the Guardianship Committee for Foreign Settlers of the Southern Region of Russia (1818). It oversaw all foreign colonies within the Kherson, Katerynoslav, and Taurida governorates, as well as the Bessarabia region. In addition to managing the organization of colonies and supporting their economic development, the committee was granted powers equal to those of the provincial administrations, including supervisory, fiscal, police, judicial, and correctional functions. It was subordinate to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and, from 1837, to the Ministry of State Domains. Administration was carried out through three guardianship offices in Odesa, Katerynoslav, and Căușeni (1818–1833), as well as through overseers and elected officials. The committee was headed mainly by Baltic Germans, including E. von Hahn, Baron von Rosen, Baron von Mestmacher, A. von Hamm, F. von Lysander, and V. von Oettinger. The committee analyzed the economic activities of the colonies and, to disseminate specialized and innovative knowledge in agriculture and crafts among the German colonists, published a German-language newspaper from 1846 to 1862. As subjects of the Russian Empire, German colonists were bound by the general norms of Russian law, just like state peasants.

As subjects of the Russian Empire, German colonists were bound by the general norms of Russian law, just like state peasants. The legislative acts regulating colonial life were consolidated in the Statute on Foreigners’ Colonies in the Empire (1857).

The legislative acts regulating colonial life were consolidated in the Statute on Foreigners’ Colonies in the Empire (1857). In 1871, radical changes transformed the status of the colonists and their administration: they became peasant-proprietors, the guardianship bodies were abolished, the colonial districts dissolved, and volosts were established in their place. Administration was henceforth carried out by the regular provincial and county authorities.

In 1871, radical changes transformed the status of the colonists and their administration: they became peasant-proprietors, the guardianship bodies were abolished, the colonial districts dissolved, and volosts were established in their place. Administration was henceforth carried out by the regular provincial and county authorities. By that time, in the three governorates, there were more than 190 German colonies with a population of 150,000 people of both sexes on state-owned lands, and nearly as many colonies on purchased and leased lands. In total, they possessed more than one million desyatinas of land.

By that time, in the three governorates, there were more than 190 German colonies with a population of 150,000 people of both sexes on state-owned lands, and nearly as many colonies on purchased and leased lands. In total, they possessed more than one million desyatinas of land.